Submitted by Rainie on

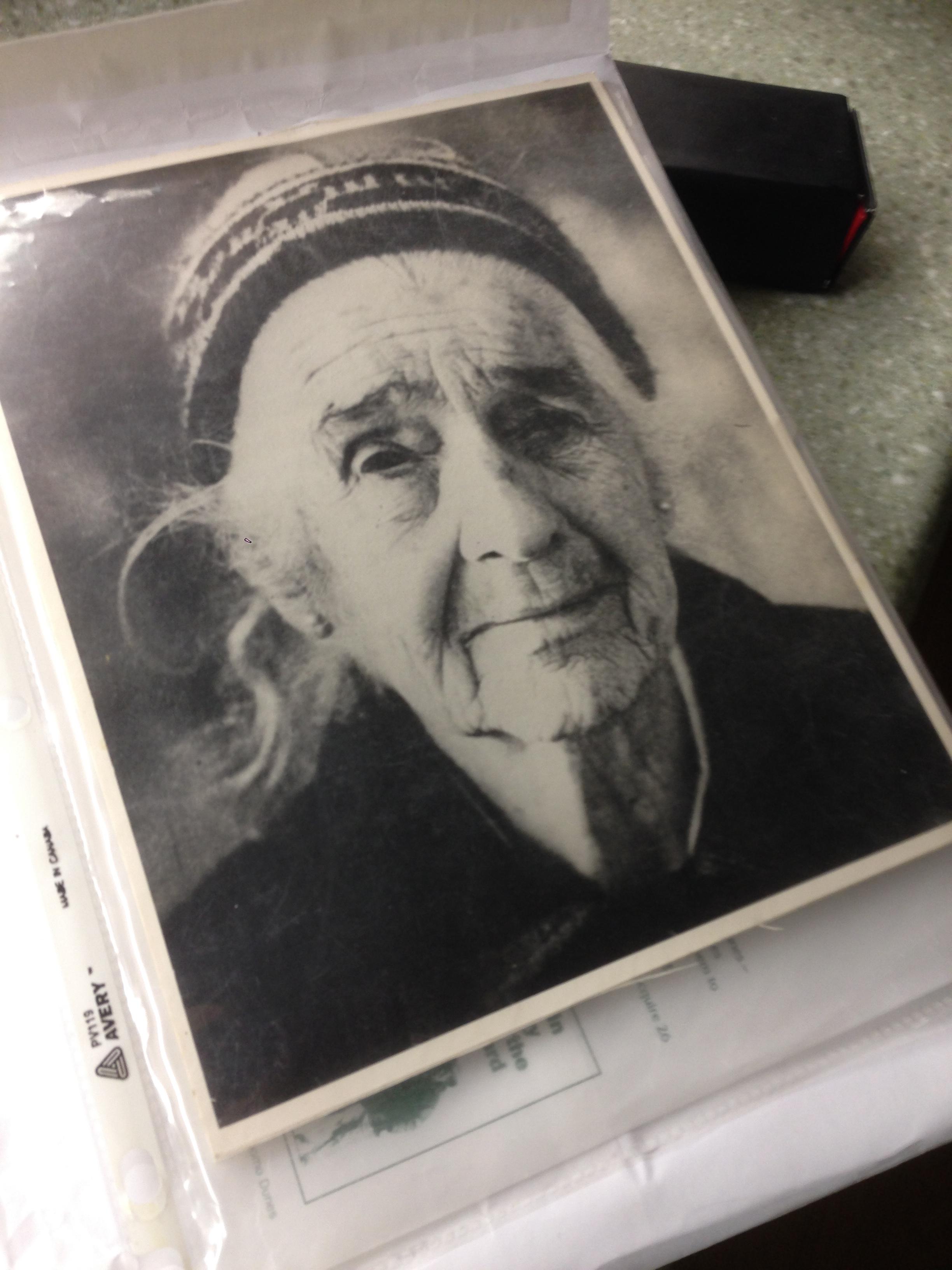

She was born in Germany on a feudal-like estate. There she spent her childhood, farming and working the land with her parents and thirty other families. Later, at an age when other girls were traditionally sent to finishing school, economic considerations caused her parents to enroll their daughter in a gardening school instead. She flourished in this setting, enjoying the freedom of being out-of-doors, working with her hands planting and growing crops alongside her peers. Here she was to develop the skills she would use for the next six decades.

As an adult woman she married, and with her husband, purchased a 3000-acre ranch on the coast of California in Monterey. For a number of years they operated the ranch together, where they spent long days riding horseback and herding cattle. During this time Gerda became familiar with the native plant communities. Her marriage did not last however, and when it ended Gerda refused to leave her coastal home. Her connection to the land, and the native flora, became a driving force in her life.

Age and circumstances required a change in livelihood. The need to produce a new source of income prompted her idea to grow the plants that she had seen naturally occurring on her property. Believing in their value, she began by producing ferns and monkey flower. Once propagated, she loaded the plants into her automobile, and driving to local nurseries, she sold them. Periodic droughts in the years that followed generated a new regard for these natives. Gradually the nursery grew, as did organizations with an interest in promoting native California plants.

Gerda herself influenced the success of the Santa Clara Valley Chapter of CNPS and in 1980 she became a Fellow of the California Native Plant Society. For over fifty years she actively managed the nursery, being the first to implement a demonstration garden for natives and producing the largest list of native species available in the state. Her life style and her strong work ethic attracted a steady stream of plant-minded individuals. Having received encouragement to develop their areas of interest, those who worked beside her went on to become growers, botanists, teachers, writers, and directors of gardens and estates.

Yerba Buena Nursery developed a reputation for growing any native plant that interested Gerda, and her entourage. Every trip into the wild or to Botanic Gardens resulted in bringing seeds and cuttings back to the nursery, even the rare and obscure. As a result Yerba Buena Nursery became known for carrying native plants that are difficult to produce, and not found in other nurseries.

My initial visit to Yerba Buena Nursery, with my husband, was followed by a decade of absence. Then in the late eighties, I visited again. A steep winding road, shaded and lined by oaks, led to the nursery entrance. Wood framed houses, built on stilts dotted the hillsides. I stayed several hours, had tea and biscuits in the tearoom, and purchased several five-gallon Malacathamnus. Returning home to Arroyo Grande I planted these the next day, near my front gate.

Visiting Yerba Buena again was like stepping back in time, and to what might be considered the essentials of life and happiness. I have memory of seeing a very old wooden table used to take cuttings, and perhaps a place to gather Gerda’s like-minded protégés in studious conversation. The edges, worn smooth and rounded, fed into the concave top surface. This one, lone table spoke volumes about the hours those young people might have spent with their influential mentor. Gerda Isenberg was a Quaker. She sought a simple existence. As Judith Lowry said at the Out of the Wild into the Garden symposium of 1997 she “was a woman able to grasp the beauty and integrity of California Native Systems and work to preserve them”. I know that her presence, her story, and her nursery made a deep impression on me.

May 2005

Rainie Fross